Depression became a normal part of my everyday vocabulary when I was twelve. I remember Newsweek did a cover story on Prozac back then. Upon reading the article, so many things began to make sense. At some point during elementary school, I suddenly became very shy. It came to such a state that simply greeting other kids was agonizing. Saying hello and good-bye to my neighbor’s daughter on the short walk to and from the school bus stop was painful. Before this time, my mother used to say I was outgoing and tiao pi, or mischievous. This made my grandfather remark that it was hard to believe I was a girl because I acted so much like my Uncle James, whom I adored, when he was young.

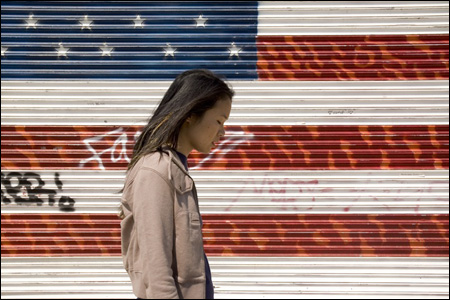

I don’t know what caused me to become so reticent and tongue-tied in public. This crippling shyness remained with me throughout elementary school, leaving me isolated and silent. It was not uncommon for me to go days without speaking more than a few words. Perhaps because little Asian girls were (and are still) expected to be shy, my silence was not considered a problem by anyone. I didn’t cause any “trouble.” And yet, a part of me knew that whatever it was that was holding me back wasn’t because I was Asian. I saw other Asian kids, including my sister, who had no problems talking and laughing in public, who weren’t afraid to go outside, who acted like normal people. This made me wonder what was wrong with me and why I couldn’t change. I developed suicidal ideation, although I didn’t know that was what it was called then. I became convinced that my life was hopeless.

Learning about depression made me realize that what I was experiencing had a name and that it was a condition that affected many people, not just me. There was help available through medication and counseling. This was further enforced in my mind when I went to college and had many friends and classmates who were diagnosed with depression and other mood disorders. They had received treatment at the campus health center. In fact, it was harder to know someone who wasn’t on anti-depressants than to know someone who was. Even though I was in a relatively safe environment that did not stigmatize mental illness, it was not until I had my own health insurance that I was able to get the treatment that I needed. When I first tried to broach this topic with my parents, they reacted with anger, disbelief, and ultimately, denial. To my parents, depression was not something that existed and anti-depressants were dangerous to take. I, too, harbored fears about going on medication that had so many side effects (really, if you look at the list of side effects, you wonder how in the world this is supposed to make you better). I was also concerned that the medication would “change” me, that I would be somehow cheating by not suffering enough. However, as one therapist pointed out, taking medication isn’t “cheating” or getting an “unfair advantage” — it just tries to help you be at the same level with others.

Although I have no wish to give to Big Pharma for the rest of my life, for now, I’ve come to accept that my new normal is to be on medication, possibly for a long time, and to see a therapist on a regular basis. Perhaps I’m fortunate that I’m one of the ones who have responded positively to medication, despite my lingering skepticism about the psychopharmacology industry. I probably would be worse off than I am now without treatment. Although they still ask when I can no longer take my medication and if I’ve tried going off of them, my parents have since come to understand that I am receiving treatment, even if they don’t entirely understand depression and still distrust medication. My former therapist was right though. Medication doesn’t bestow any kind of special advantage, nor did it turn me into a zombie or a former shell of myself, as I had feared. It only brings me as close to being “normal” as I can be. Perhaps in the end, that is all that I can expect of it.

Eugenia Beh

Electronic Resources Librarian

Texas A&M University

APALA President, 2013-2014

Resources

MentalHealth.gov: http://www.mentalhealth.gov/

NAAPIMHA (National Asian American Pacific Islander Mental Health Association): http://naapimha.org/

Friends Do Make a Difference Campaign: http://naapimha.org/friends-do-make-a-difference/

Raising Awareness About Mental Health and Suicide Prevention in the AAPI Community: http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2013/05/10/raising-awareness-about-mental-health-and-suicide-prevention-aapi-community

Suicidal Thoughts Among Asians, Native Hawai’ians or Other Pacific Islanders: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2K13/Spotlight/Spot118-suicidal-thoughts.pdf

The It’s Ok Campaign: http://itsokcampaign.org/

Chai (Counselors Helping South Asians/Indians, Inc.): http://chaicounselors.wordpress.com/

Asian American Mental Health, Ramey Ko story (by a friend of mine): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VvvlLdHS1FA&feature=youtu.be