by Jerry Dear

According to mythologist Joseph Campbell, following one’s bliss is a lifelong venture, one that ultimately defines who we are: “If you follow your bliss you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living . . . . follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be. If you follow your bliss, doors will open for you that wouldn’t have opened for anyone else.” By pursuing her bliss as a librarian, historian Judy Yung uncovered buried truths that unveiled hidden chapters in the annals of Chinese American history and beyond.

Yung launched her library career at the Him Mark Lai/Chinatown Branch of the San Francisco Public Library in the early 1970s. Identifying a gap in the field of Chinese scholarship, she sought to build a Chinese interest collection that addressed the needs of the community and later developed the Asian community library in Oakland (now known as the Asian Branch Library). Today, these libraries house evolving Asian interest collections that encompass the culture, history, and heritage of the Asian American experience.

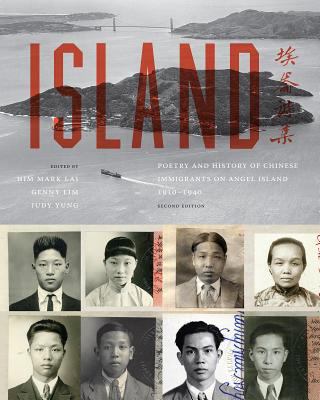

Yung’s work spans a prolific range of topics in Chinese American history through scores of research articles, books, interviews, and documentary films. Initially published in 1980, and having undergone extensive revisions, her seminal work Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910 – 1940 chronicles the collective voices of generations of Chinese immigrants barred from becoming naturalized citizens due to discriminatory, anti-Asian laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. In conjunction with the “dean of Chinese American studies” Him Mark Lai and poet Genny Lim, this pioneering research documents the enduring legacies of the Chinese and their intimate experiences embodied through poems carved on walls of the Angel Island detention barracks. These poems proclaim the anguish and perseverance of Chinese Americans during the early twentieth century, who were so close, yet so far, in achieving the American Dream. Four decades later, Yung collaborated with Professor Erika Lee from the University of Minnesota to illuminate stories of Japanese picture brides, Filipino repatriates, Korean students, Russian and Jewish refugees, and other immigrants in Angel Island: Immigration Gateway to America (2010)—a groundbreaking work that coincided with the centennial of the Angel Island Immigration Station.

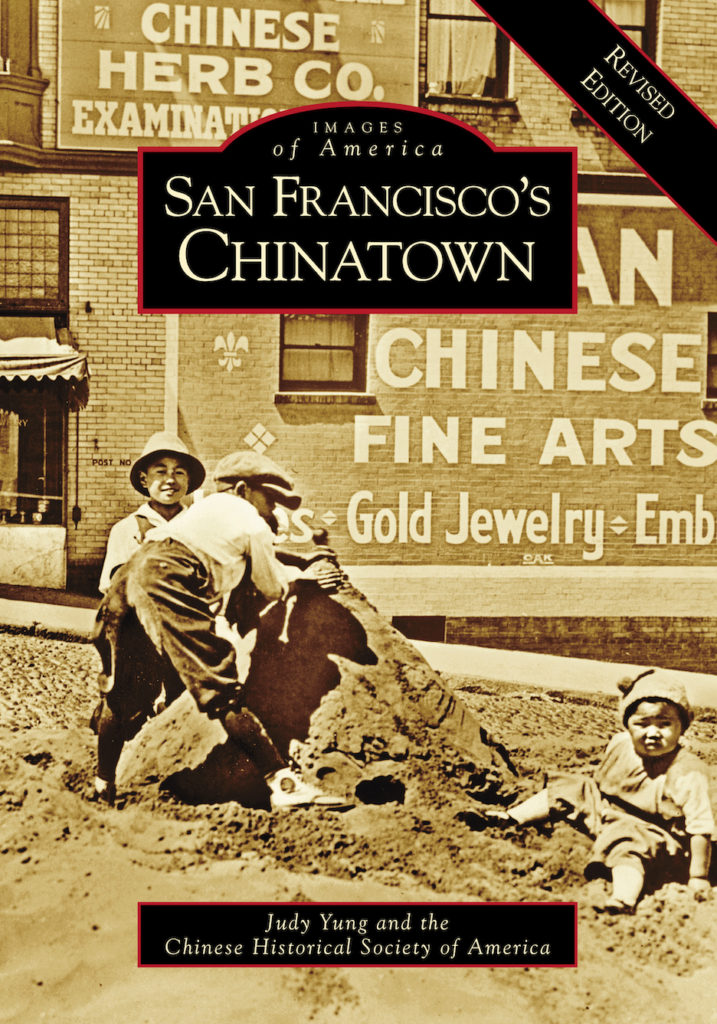

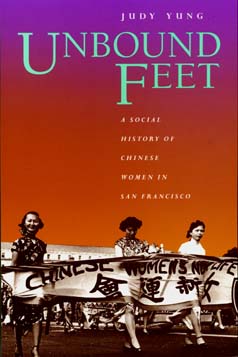

In addition to documenting oral histories of Angel Island immigrant detainees, Yung researched other facets of the Chinese American experience, starting with the sociopolitical history of Chinese American women in Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (1995) and Unbound Voices: A Documentary History of Chinese Women in San Francisco (1999). A decade later, she co-edited Chinese American Voices: From the Gold Rush to the Present (2006), a companion book that incorporated male voices into this rich mosaic of experiences. Even in retirement, she nurtured her passion by supporting other researchers like Eleanor Swent to identify more recent immigrant stories in Asian Refugees in America: Narratives of Escape and Adaptation (2011) and also met regularly with her close friend and historical fiction writer Ruthanne Lum McCunn. In collaboration with the Chinese Historical Society of America, she compiled a photo-history of San Francisco’s Chinatown (2016), offering an insider’s perspective to the largest community of Chinese outside of Asia.

Yung also served on Asian American film projects as a consultant and project advisor, often guest appearing to contribute extensive insight on Angel Island immigrants, the historical formation of San Francisco’s Chinatown, and other Asian American community-based topics: She interviewed a San Francisco Chinatown garment worker in Arthur Dong’s Sewing Woman (1982); Felicia Lowe’s Carved in Silence (1988) presented dramatized recreations and interviews of Angel Island detainees; Separate Lives, Broken Dreams (1994) explored the devastating impact of the Chinese Exclusion Act; Bill Moyers’s three-part television series Becoming American: The Chinese Experience (2003) traced the historic saga of Chinese Americans through their struggles and triumphs in pursuing the American Dream. Most recently, Reverend Harry Chuck’s Chinatown Rising (2019) highlighted the urban housing crisis on San Francisco’s Chinatown amidst the backdrop of the Asian American movement in the 1970s. Through these films, Yung expounded on the lived experiences of Chinese Americans with keen insight to demonstrate their resourcefulness, tenacity, and resilience in the face of systemic racism.

An intrepid librarian, researcher, scholar, author, and historian, Judy Yung, along with pioneering historians Him Mark Lai and Philip Choy in Chinese American studies, established core texts used in ethnic studies courses, challenging the Eurocentric master narrative of American history. At the core of her librarianship, she championed building diverse collections, resources, and staffing to meet the needs of the Asian American community: “We must meet community needs with books, magazines, films, records . . . of interest and importance to them. The staff must develop community contacts to assess library needs before material is purchased. The staff must have the language skills, life style, and sensitivity that the Asian communities can relate to” (East/West, 2/11/1976).

Although we have lost a treasured historian, colleague, mentor, and dear friend, Yung’s legacy continues to educate and empower future generations, highlighting deeper truths that complement the history and heritage of America. May she rest in perfect peace, having embraced her bliss to fulfill her life’s purpose.

At ALA Midwinter 2021, the ALA Council adopted a memorial resolution (M#6) in honor of her many accomplishments to the field of librarianship, ethnic studies, history, women’s studies, and beyond. Read more stories and share reflections at the Judy Yung memorial blog: judyyung.wordpress.com