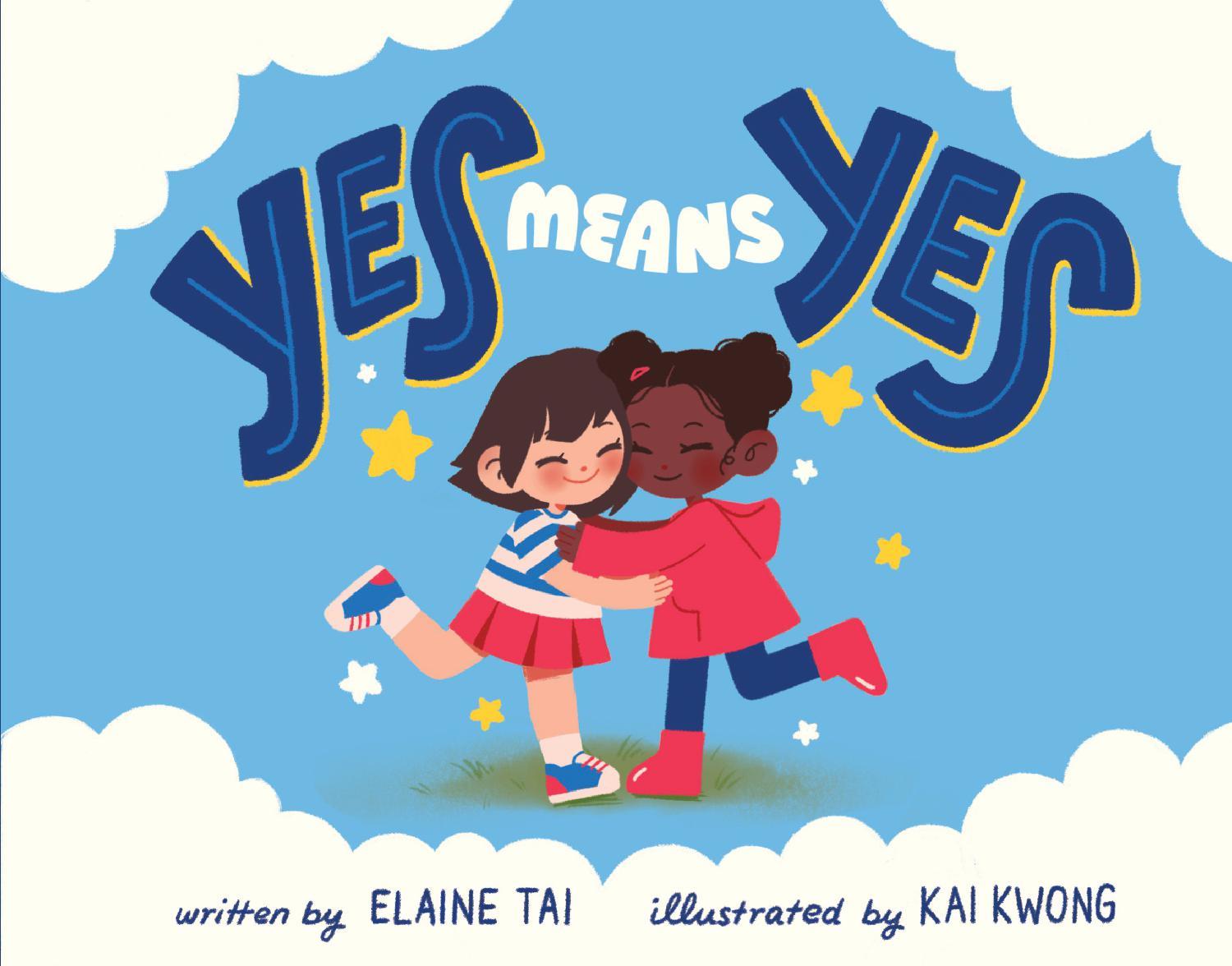

Yes Means Yes

By Elaine Tai

32 pp.

Illustrated by Kai Kwong

ISBN 9781667822846

Despite its entry into U.S. popular discourse, consent in sexual interactions is an idea with which many of us continue to struggle, as some are unable (or simply refuse) to divorce from regressive gender ideologies. These individuals are ill-prepared to understand how different types of power relations influence what, how, and if we communicate with each other. If this way of thinking is new to some, there are those of us who bandy around the term ‘intersectional’ so that it loses much of its analytic salience. It makes sense, then, that even among the more open-minded there is a continuing disregard of how consent–and relatedly, choice–operates for those who hold multiple-minoritized identities. As we shift towards a more complex understanding of the concept perhaps it’s time to review a core aspect of all social relations: respect.

I mention all of the above precisely because I believe that respect and accountability are crucial to a healthy society. From an emphasis on consent education among adults, it’s refreshing to observe a wider conversation that includes kids and teens. Yes Means Yes joins the growing body of works for children providing guidance on asserting and navigating boundaries in a variety of contexts. Interestingly, the picture book almost never saw the light of day. Thank goodness for author Elaine Tai’s tenacity. When it comes to resources on foundational concepts, Tai asserts that one can never have too many. I heartily agree.

A book for developing readers, Yes Means Yes pairs straightforward text with Kai Kwong’s whimsical illustrations. The book starts with an adult character’s gentle reminder about bodily autonomy; the child has a right to their preferences, but so do others. From there Tai and Kwong go on to explore specific situations. The first example depicts a Black girl with a questioning look directed towards the White classmate seated behind her; the latter is about to touch their hair. Tai offers a few ways to prevent this microaggression, including the use of compliments. The suggestion of an imaginary force field was slightly jarring; as an adult-aged reader, I was reminded of how borders are deployed to mark outsiders and enemies. At the same time, it makes sense to use this kind of figurative language when explaining complex topics to younger learners.

Other stand-out scenes depict interactions with adults. Expected to be compliant, children may face challenges not only with “stranger danger” but also when interacting with family members. Yes Means Yes encourages children to honor and voice their feelings, and trust that their adults will support them. In one instance, a grandfather offers a high-five instead of a hug. Another illustration depicts how a child can further advocate for themselves in situations where the otherwise trusted adult pressures them to interact. The adult appears to empathize with the child and affirm their choices.

We need only review our experiences with intergenerational trauma to understand that this kind of support isn’t always available. Maybe our caregivers, as kids, learned to equate vulnerability with weakness. Lacking models for healthy self-expression, they impress similar beliefs on the youth in their orbit. Additionally, many of us from Asian diasporas and immigrant communities are likely well-versed in tempering our self-expression in service of interpersonal harmony; still some of us have deployed this as a survival strategy. So ingrained are these habits that we may reconsider them only much later in life, if we reflect on them at all. We can be grateful, then, for a book like Yes Means Yes, which teaches kids and adults alike that social-emotional literacy is for everybody.

Review by Charisma Lee, editing assistance by Danica Ronquillo.

Book reviews and author interviews featured on APALAweb.org are reflective of the reviewer and interviewer only and are conducted separately from and independently of APALA and the APALA Literature Awards Committee and juries.