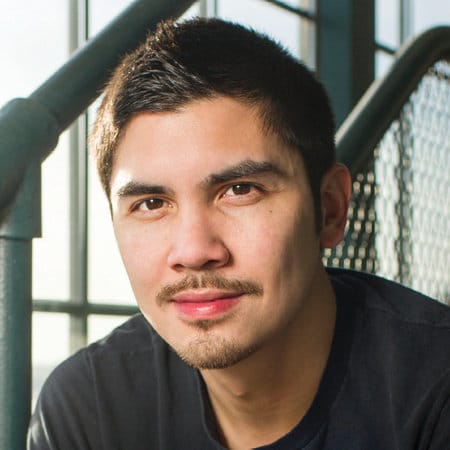

Randy Ribay is a teacher and author whose books include An Infinite Number of Parallel Universes, After the Shot Drops, and Patron Saints of Nothing. You can find his work at Powell’s, your local bookstore, or your local library. He is interviewed here by APALA member Jaena Rae Cabrera.

Jaena Rae Cabrera (JRC): Please introduce yourself and briefly describe your literary work and career path to date.

Randy Ribay (RR): What’s up! I’m Randy Ribay (pronounced /REE-bye/). I was born in the Philippines and raised in the Midwest. I earned my BA in English Literature from the University of Colorado at Boulder and my master’s degree in Language and Literacy from Harvard Graduate School of Education. I’m the author of An Infinite Number of Parallel Universes, After the Shot Drops, and Patron Saints of Nothing, which was selected as a 2019 National Book Award finalist for Young People’s Literature. In addition to writing, I teach high school English full-time in the San Francisco Bay Area.

(JRC): How has your own identity as an Asian American influenced your writing? The diversity of your readership?

(RR): I never read a book by or about a Filipino, Filipinx American, or biracial person until I got to college. Having grown up in a somewhat assimilationist household and in a mostly white suburban community, the result was an underdeveloped understanding of my own racial identity and all of the colonialist consequences that comes from that. It was those books I would eventually come across in college that helped me learn and come to love the Filipino side of myself.

As I started writing, I took seriously Toni Morrison’s advice to write the books you want to read, so I started writing YA about characters who looked like me as both a way of exploring that side of myself and offering my perspective as — to borrow language from Rudine Sims Bishop — a mirror or window for teens coming up today, especially Filipinx American teens.

(JRC): What drew you to fiction?

(RR): Initially, it was just a love of entering other worlds, the limitless sense of possibility of imagination. Eventually, I came to appreciate the power stories have to shape us and our world by conveying the multiplicity of human experiences.

(JRC): Can you describe an instance when libraries and/or archives played a beneficial role in your work?

(RR): I’m working on a project right now that requires some pretty obscure historical information, the kind of stuff you can’t find at Barnes & NobleAmazon, eBay or even on the internet. Luckily, I have access to a well-stocked and well-staffed university library that allows me to find all these books and articles that I otherwise would not be able to due to rarity or cost.

(JRC): What advice would you give librarians and information professionals, especially those from diverse backgrounds who work with diverse populations, to promote literacy and readership?

(RR): I’d say find ways to really get to know your community, be part of your community, and advocate for your community. If you build genuine connections with people and they see that you’re truly there for them, I think they’ll be more interested in what you’re trying to do, in regards to promoting literacy and readership, than if you’re just passively expecting them to come to you.

Beyond that, while it’s important to get books into peoples’ hands, it’s equally important to find ways to help create pathways for people from traditionally marginalized backgrounds to get into librarianship. What are the barriers? What can you do in your specific corner to reduce those barriers where you are? How can you work with others to reduce those barriers at a systemic level?

(JRC): What message would you give to librarians/archivists/writers/artists regarding their value in the field you work in?

(RR): It’s invaluable.

(JRC): What current trends in publishing, reading habits, and distribution of library materials concern you the most? What thoughts do you have on these trends?

(RR): As a writer and avid reader of young adult books, I know the stories written for teens are more diverse and of a higher quality than they’ve ever been. Despite this, as a teacher for the last decade and a half, I’ve seen firsthand the decline in the amount of time students read books on their own outside of what’s required for school. While I think this is partially due to increased time spent on visual and social media, I think it’s also because the books they’re exposed to in school are often still the same crusty, old stories many of their grandparents may have read in school. Basically, what we’re giving them isn’t as interesting as what they can find on their phones or consoles. Inside and outside the classroom, we need to find ways to connect kids with the relevant, powerful stories that are out there — and these stories are going to be different for every kid. I believe that there’s a depth to longform stories told directly through written or spoken language that’s unmatched in other forms of media and that these stories can speak for themselves if we only help kids find them.

(JRC): What are your thoughts on the role/significance of poetry in a publishing/reading world dominated by prose and audiovisual media (film, television, videos, even social media, etc.)?

(RR): Even though I publish prose fiction, I started writing by writing poetry. It taught me to love the sound of language, the way certain words feel when arranged in a certain way, the power of the image. I still love reading it and go back to it all the time because, as I heard another writer say once, poetry reminds us of what language can do.

(JRC): What are your thoughts on e-books and libraries? Perhaps in terms of use, circulation and access?

(RR): I’m a frequent user of my library’s e-books, audiobooks, and graphic novels through the Hoopla and Libby apps. I’m not too clear on the inner-workings of these systems, but certainly the more free access and diversity of content, the better for the public. There are many, many books I’ve read through Hoopla and Libby that I would probably have never read otherwise.

Editing assistance by Shelly Yuki Black.