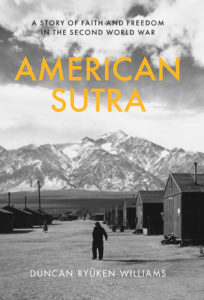

Duncan Ryūken Williams is currently Professor of Religion and East Asian Languages & Cultures and the Director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture. He has also been ordained since 1993 as a Buddhist priest in the Soto Zen tradition and served as the Buddhist chaplain at Harvard University from 1994-96. He is the author of The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Soto Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan and is the editor/co-editor of seven volumes, including Hapa Japan, Issei Buddhism in the Americas, American Buddhism, and Buddhism and Ecology. He has translated four books from Japanese into English including Putting Buddhism to Work: A New Theory of Economics and Business Management. His latest book is American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War.

Molly Higgins (MH): Would you like to introduce yourself and your literary career to date?

Duncan Ryūken Williams (DRW): My main field of research is Buddhist studies and originally, I really focused on Japan. My first book was about Zen Buddhism from about 1600 to 1868,a very historical book called The Other Side of Zen. I’ve edited many other volumes about Japanese Buddhism as it enters the early modern period and what happens when it bleeds out into the world. Issei Buddhism in the Americas looks in a hemispheric way at what happened in Brazil, the United States, and Canada, with the migration of Buddhism from Japan to the Americas alongside immigrant communities. Those were some indications that eventually I would get to do this book, American Sutra, which is about, very specifically, Japanese American Buddhist communities and what they went through during World War II and how that history says something about what the incarceration experience was all about, but also how something called American Buddhism got formed in the crucible of war and how looking at all of that helps understand how race, religion, and American belonging come together.

MH: At the beginning of the book you talk about how you came to this story and I would love for you to talk a little about that.

DRW: One of my graduate school advisers passed away just after I finished my dissertation and his wife asked me to help put some of his affairs in order. I started pulling things out and taking a box or two to her house every day. I spent a couple of days on this and in between drafts of dissertations I found something with his name on it, Nagatomi, in Japanese, but I could tell it wasn’t his handwriting. His calligraphy looked different. And I came to discover that this was his father’s World War II diary and personal notes. He was a Buddhist priest who spent who spent the duration of World War II in a camp in California–Manzanar–and he had written these notes to himself to give dharma talks, or sermons, on Sundays. In his diaries he would talk about all kinds of things that were happening in camp from his point of view as a Buddhist priest.

Because I grew up in Japan and didn’t have any family connected to this history, it took me a while to understand the value of a diary like this, but translating portions of it for my professor’s wife really got me into wanting to learn more and ultimately her telling me the story of her family in Madera, California. Her dad, being on the board of the local temple, was targeted by the FBI as many Buddhist leaders were in the days after Pearl Harbor. Her dad wanted to show loyalty to America because the FBI kept on interrogating him. Although their family and community had nothing to do with the Pearl Harbor attack, they felt responsible, or were under suspicion, and so her dad started burning everything that had Japanese language on it or was made in Japan. He asked his wife to find a box that he could put some particular documents in and he buried this box in the backyard. And for her, as a ten year old girl, she was like “What could possibly be more important than my dolls?” and it turned out that he had a Buddhist sutra, or a Buddhist scripture, that had been handed down from his father and grandfather–through generations–and he felt like he couldn’t put that in that fire. Also, as a leader in the local Buddhist community, as a board member, he had all the board meeting minutes from the founding of that temple in Madera California, and again, he felt like he couldn’t put that in the fire because it wasn’t his personal property, but also because it represented the community’s history in America. So he had these two things that he buried in the ground.

Somewhere, this scripture and the teachings it contained and the history are lying within the soil of California. And this story prompted in me this interest to try and understand what it means for a family to say, in a situation where they’re feeling under pressure, where it’s war time, where people are thinking that they look like the enemy, to say that they belong, even if their government says that they don’t belong. And try as they might to burn away their Japanese-ness, they can’t burn away their faith, their Buddhism. There are many, many families, thousands of families who tried to assert that you can be both Buddhist and American at the same time. That was the question that was driving me as I wrote this book–how did this come to be, this thing called American Buddhism? In the camps, behind the barbed wire.

MH: So then, for someone who, as you say, has less of a family connection to the story, do you think that brings a different perspective to this story than some of the other scholarship that’s been done around this?

DRW: I’m not sure its my personal perspective, but I think what the book might be contributing is its focus on Buddhism, which I have some expertise in. And I have the ability to also read Japanese language materials. And I think that combination perhaps has not been emphasized before. I think that in Asian American Studies, in general, Asian language materials–diaries, records, and so on–even in the Vietnamese American or Chinese American experience hasn’t been highlighted as much as materials written in English. And so in the WWII Japanese American story, the story often gets told, not from the first generation of people who are in their thirties or forties or fifties or older, but people who are younger, in their teens or twenties, or even people who were kids in their camp days. It gets told from a second generation or American-born, U.S. citizen perspective that is extremely valuable because two thirds of that population were kids and teenagers into their twenties, but the English speaking sector of that community, and sometimes, in terms of religion, the English speaking, Christianized Nisei, that kind of perspective has most often taken the main part of the picture even though two thirds of the community was Buddhist. I think we’re missing the Buddhist voice as well as the voices– because they didn’t want to talk about it so much–of the parents, after they experienced the loss of their business or farm or everything they had worked for decades prior to Pearl Harbor. That perspective of the older generation of people has been slightly missing in the telling of the WWII Japanese American story. So I hope that my book adds to that perspective.

MH: When I was studying the Japanese American internment, I felt like a lot of the narrative was about how do we get to reparations? And how do we get to activism? I found that perspective very, very valuable, but I think this book does something different.

DRW: Right, and I think that the Christianized, English-speaking, Nisei perspective was one that, in the redress movement, was necessary and tactical to highlight, to make the political case about what happened– to emphasize that we’re just like most Americans who are Christian or just as English speaking. That was a tactical thing to do for redress but it didn’t tell the whole story and I think that was what I was trying to supplement.

MH: You conducted over 100 oral histories while researching this book and only a small section of them make it into the book. Do you think you’ll ever make them available to a wider audience or do something else with them?

DRW: Several years ago this book was a 700 page monster of a book, and today, not including the end notes and index, it’s about 350 pages. I cut in in half. A lot of it was about the prewar years. One of the points that I really wanted to make in the book is that the targeting, the racial as well as religious animus that comes up in this book didn’t just happen suddenly. There’s a lot of people who look at that portion of history and say it was a combination of racial animus, why the Japanese Americans were targeted in a way that German American and Italian Americans were not, a lack of political leadership in terms of protecting constitutional values, and then war hysteria. And I always found the war hysteria one to be not true at all. The planning of and targeting of this community–building files, registries, lists of people to arrest in case of war with Japan, and surveillance of Buddhist temples–was happening years prior to Pearl Harbor. The Navy in the Pacific had been quite concerned for years about a naval attack on Pearl Harbor, so they had contingency plans set in place for years ahead of time. I’m tempted at some point to write a companion volume about the prewar period.

MH: If this book could influence the public dialogue when it comes out, how do you hope that it would influence people?

DRW: There’s a story that I heard from an imam of the Honolulu mosque, the biggest Islamic center in Hawaii. And of course, this is a while back but it represents this post-9/11 and onward rise of the fear of Muslims. So, in the days after 9/11 this imam was telling me that this 90 year old lady, this Japanese American lady, would come during the evenings and just stand in front of the mosque. And eventually, after she was doing it for a couple of days, he went to ask her “Hello, I’m the imam here. What are you doing here?” And she was like “Oh, I’m protecting your mosque.” And she shared the story of how Buddhist temples came under attack after Pearl Harbor–a number of arson cases and shotguns being shot into the temple and things like that. She wanted to make sure that didn’t happen to his mosque. On one hand he found it strange–how would a ninety-year old Japanese grandma really offset an attack on the mosque? On the other hand, he was so moved by the idea that somebody who was from a completely different ethnic,racial, and religious background and age would see the connection. And I think that’s what I hope the book will do.

It’s not just a book for Asian Americans and Buddhists. I hope it will be read more broadly by people from a variety of faith traditions or by people who are not of a religious tradition who see some value in the idea of pluralism and multiplicity as a necessary part of what is America and find ways to connect different communities with each other.

American history is a pendulum. If this book had come out, say, when Barack Obama had first been elected it might have been a book that said “Oh, America has this arc towards the perfection of the Union, in which we now have the first black president.” There would have been a certain take on the book. But this book is coming out in our age, on the other side of the pendulum swing, amidst more nativist ideas that presume and assert this idea of a singular vision of America as a white Christian nation in which exclusion of immigrants is a way to protect that vision, and to protect people who carry that vision as well. It’s also about internally, among the citizenry, making a double standard in which a certain group of people are deemed second class citizens.

The only hopeful thing I can say is that Buddhism teaches everything is impermanent, and pendulums do move back. But they move back because people remember. People who stood up when their own government told them that they don’t belong. They found a way to say, “We can be both Buddhist and American at the same time. We can fulfill that promise of religious freedom in the Constitution just by persisting.” I don’t want to end on a despairing note.

MH: Transitioning a little bit, since we’re a library organization, who else should we be reading?

DRW: There’s a new book out this February via Yale University Press, called American Dharma, by Ann Gleig. It’s a book thinking through contemporary Buddhism, for example the ways that mindfulness has become so ubiquitous, and the relationship between secular and Buddhist mindfulness. She does a really good job of interrogating how that all happened and how Asian and Asian American communities from which these all come from–Theravada, Southeast Asian, and Vietnamese like Thich Nhat Hanh–how that got translated into something like mindful products at Whole Foods or mindfulness classes at Google. It’s a great book that tells that story and does it in a very smart way.

MH: You’re being interviewed for an audience of progressive Asian American librarians. Do you have any thoughts on libraries and their place in supporting diverse communities?

DRW: I spent a lot of hours in a lot of different kinds of libraries to do the research for this book. Whether it’s Asian or Asian American resources in libraries, it’s been one of the things that I’m keen on supporting, especially because I come from California. I want Asian language resources in libraries as well as Asian American stories, American stories, collections that have primary resources, gifts from families that have important stories to tell. 2030 is the year when California will become majority Asian/Latino and minority black/white and in terms of the history of America, the black white binary has been so dominant in how we think about race. Asian Americans have always been like, “Do we elide into whiteness? Do we resist it into blackness?” I think there’s something about Asian American peoples, cultures, religions, and materials that would go into libraries–stories–that deserve a place on its own. I hope not only for future researchers who would come after me, but for the communities themselves to recognize that their histories are important histories of local, state histories or regional histories, and ultimately national histories as well.

Editing assistance provided by Shanna Kim.