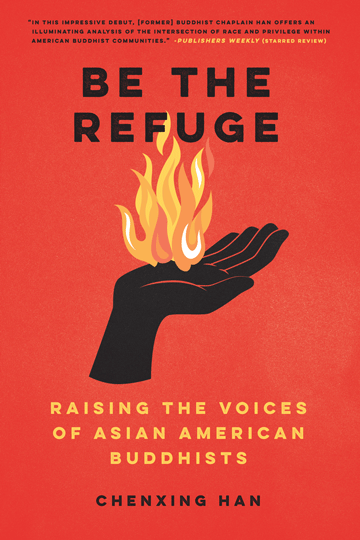

Chenxing Han’s first book, Be the Refuge: Raising the Voices of Asian American Buddhists, comes out January 26, 2021. You can find it at Powell’s, your local bookstore on Bookshop.org, or your local library. She is interviewed here by APALA Treasurer Jaena Rae Cabrera.

Jaena Rae Cabrera (JRC): Please introduce yourself and briefly describe your literary work and career path to date.

Chenxing Han (CH): My name is Chenxing Han and I’m a writer currently based in the San Francisco Bay Area. My first book, Be the Refuge: Raising the Voices of Asian American Buddhists, will be coming out with North Atlantic Books on January 26, 2021. I’ve published articles, book chapters, and other pieces in Buddhadharma, Journal of Global Buddhism, Lion’s Roar, Pacific World, Tricycle, and elsewhere. Born in Shanghai and raised in Pennsylvania and Washington State, I came out to the Bay Area for college and stayed on for grad school. After earning my bachelor’s from Stanford University, I worked in the nonprofit sector before pursuing an MA in Buddhist studies from the Graduate Theological Union and a certificate in Buddhist chaplaincy from the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Berkeley. I completed a yearlong chaplaincy residency at a hospital in Oakland after getting my master’s, and it was this education in spiritual care that inspired me to move to Asia and focus on writing. Most of Be the Refuge was written in Taiwan, Cambodia, and Thailand; my husband and I were living in Bangkok when the pandemic turned our “month long visit” to the Bay into an indefinite stay. I’m currently working on a memoir about Buddhist chaplaincy, grief, and spiritual friendship.

(JRC): Do you think your personal identity influences your writing and/or the diversity of your readership? How?

(CH): Recently I was sifting through old English class assignments from my K–12 public school education, and it struck me how the characters of my stories never bore anything besides American or European names, never ate any of my favorite foods (in those pre-vegetarian days, fish-head soup, 炒年糕, jellyfish salad). I’m not entirely sure when I started thinking more seriously about issues of identity and diversity. Perhaps during the gap year I took between high school and college, when I taught English in Shanghai and traveled through Hong Kong, Thailand, Nepal, and Tibet. Being taken out of the American context, where I’d always felt either invisible or hypervisible in relation to the gleaming power-center of whiteness, gave me the freedom to consider my identity (and other people’s identities) in more expansive ways.

Be the Refuge is an exploration of the possibilities and limitations, the connections and contradictions, within Asian American Buddhist identity. I found the tension between “Asian American“—which connotes ethnic and cultural specificity—and “Buddhist”—a universal religion open to people of all backgrounds—to be a productive one. (I should add that “Asian American” is a contested term. I’m using it in a broad sense to mean people based in North America who trace their heritage to some part of the geographic continent of Asia.) I think my willingness to grapple with identity in all its complications invites a readership that wants to engage with identity in ways that aren’t reductive. As I learned from being a hospital chaplain, demographic information can offer helpful context, but it is never determinative.

(JRC): For those of us unfamiliar with the Buddhist community, what would you like us to know about this book?

(CH): Religion is an important but neglected dimension of the Asian American experience. We hear about the challenges and achievements of AAPIs in business, education, politics, the arts, but seldom attend to the spiritual dimension of their lives. The young adults in Be the Refuge grapple with religious, ethnic, and generational identity in ways that resonate with people who don’t share their religious, ethnic, and generational identities. Indeed, the people I interviewed in my book were not all raised in Buddhist households: some grew up Zoroastrian, Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, atheist, Christian, or mixed-religion households.

Buddhism is a minority religion in this country, but people of Asian heritage make up the majority of American Buddhists. A 2012 Pew Forum report estimates that of the 1% of Americans who identify as Buddhist, more than two thirds are Asian American. Many people are surprised by this statistic, since white meditators dominate in the American Buddhist mediascape. I wrote Be the Refuge to challenge reductionist portrayals of Asian American Buddhists as Oriental monks and superstitious immigrants. I was tired of the same old tropes and wanted to open up new modes of representation, new avenues of conversation.

(JRC): How does your background as a Buddhist chaplain inform the writing of your book?

(CH): When I wrote the first, academically oriented draft of my book, I naively thought my chaplaincy training didn’t have any bearing on my writing. It was only when I discarded that first draft and started a new book from scratch that I began to appreciate the kinship between writing and chaplaincy. Both cultivate a practice of deep listening and an integration of different perspectives. Both are humanizing forces in systems and circumstances that can be dehumanizing. In humanizing a group that is all too often reduced to stereotype or caricature, Be the Refuge serves, I hope, as a vehicle of spiritual care that sparks the kinds of heartfelt conversations the book was woven from.

(JRC): What research methodology did you use? How did you find your 89 interviewees?

(CH): I decided to conduct one-on-one, semi-structured, in-person interviews with any young adult Asian American Buddhist who was willing to talk to me. I wasn’t sure if I’d find anyone, so my list of interview questions was, shall we say, very ambitious. It included seven different sections, including an interactive card sorting activity to explore people’s Buddhist practices and a survey on Buddhist beliefs.

I put out a call for interviewees online, and also asked interviewees to recommend people to reach out to. I ended up interviewing twenty-six young adult Asian American Buddhists, broadly defined. They traced their heritages to South, Southeast, East, and West Asia; most were in their 20s and 30s; all had a connection to Buddhism but didn’t necessarily go around publicly identifying as Buddhist, for reasons I explore in the book. I was lucky to meet such a patient, thoughtful group: our conversations ranged from 1.5 to 5+ hours long! There were more people who wanted to participate, but whom I couldn’t meet in person. I adapted my interviews to an email format and received sixty-three more responses.

I was astonished by the diversity of this group of eighty-nine interviewees. They aren’t meant to be a representative group, but their perspectives help us appreciate the complexity of American Buddhism. Their voices are an invitation for more Buddhists from underrepresented backgrounds to share their stories.

(JRC): What challenges did you face, if any, in getting your first book published?

(CH): I write about this in the book itself (spoiler alert!), but it took several years to find a publisher for my completed manuscript, which was rejected by two Buddhist publishers and two academic publishers. The reasons for these rejections are surely myriad, but it’s worthing noting that Buddhist publishing in this country, like the broader American publishing industry, fails to reflect the racial diversity of this country (to say nothing about other forms of diversity). I was tempted to give up on many occasions, especially when people like me—not white, not a man, not a PhD-holder, not a meditation teacher, not a long-dead Asian monastic—are almost entirely absent from the author lists of Buddhist and academic presses. I am enormously grateful that North Atlantic Books, a California-based nonprofit publisher committed to racial, social, and environmental justice, was willing to take a chance on Be the Refuge. They immediately saw the need to publish a book featuring Asian American Buddhist voices, and I’ve been fully supported through every step of the publishing process.

(JRC): We’re always looking for more to read. Who are five authors we should be reading? Why?

(CH): I feel like I should be asking you this question, especially since I have a massive reading backlog! I will shamelessly blame this backlog on the difficulty of accessing books while living in Asia, and not on my internet browsing or sourdough baking habits.

Given the focus of Be the Refuge, I’ll limit my answer to books by authors of Asian heritage who have expanded my thinking on the Asians American and/or Buddhist experience. In the order I pulled them from my bookshelf:

erin Khue Ninh’s Ingratitude: The Debt-Bound Daughter in Asian American Literature, for showing me that literary scholarship can save lives. I’m inspired by the clarity of Ninh’s argument, the precision and beauty of her writing, the unflinching examination of (in)gratitude, filiality, debt, masochism, surveillance, power, control. I can’t wait for her forthcoming book, Passing for Perfect: College Impostors and Other Model Minorities.

Jenny Xie’s Eye Level, for exploring the frictions and fluencies of “an appetite for elsewhere,” an appetite that’s hard to satisfy in this age of lockdown. The Buddhist references are subtle but permeating. I want to dwell in the dance of samvega and pasada that sutures these poems together.

Spring Essence: The Poetry of Hồ Xuân Hương, translated by John Balaban, for beautiful, bad-ass poems from an eighteenth-century Vietnamese concubine. I love Hồ Xuân Hương’s unsanitized version of Buddhism, how she is both invested in the religion’s ideals and critical of its institutional failures. I’m so glad that Copper Canyon Press included the original Nôm script poems along with their Vietnamese transcriptions.

Duanwad Pimwana’s Bright (Arid Dreams is her other story collection), translated by Mui Poopoksakul, a picture of working-class Thailand that made me cry, for Momo the pious dog, Chong the soft-hearted shopkeeper, Kampol our five-year-old protagonist. A 2019 Nikkei Asia article puts the tally of original works of fiction and poetry, published in the United States in English translation since 2008, at: Japanese literature 363, Chinese 254, Korean 141, Indonesian 18, Hindi 12, Vietnamese 9, Thai 0 (before Pimwana’s two collections). Last year, while discussing The Bluest Eye with my Thai teacher, who helped copyedit the Thai translation of Toni Morrison’s first novel, I was struck by how easy it is to become American-author-centric in one’s reading habits.

Kim Thúy’s Ru, translated by Sheila Fischman, for lilting the American dream through the opulent sway of a Canadian teacher’s hips, for capturing the soul of memory in lotus-blossom-cradled tea, for a structure that mesmerizes like Shouchiku Tanabe’s bamboo art.

(JRC): You’re being interviewed by a librarian, for an audience of progressive Asian Pacific American librarians. What are your thoughts on libraries, and their place in building diverse communities?

(CH): The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh was my first house of worship. It was a free place for five immigrant Chinese girls to learn and play after a day of classes (and racial taunts) at our inner-city elementary school. In addition to making origami cranes from the slips of paper we were supposed to write call numbers on, I vowed to read all the books, starting with Road Dahl, until the day I realized the children’s section was not the only room in the building. I would not be a writer without the Carnegie Library and all the other public libraries of my youth. The difficulty of accessing books while living in Cambodia and Thailand, where public and academic libraries are scarce, further heightened my appreciation of these vital institutions. One of my greatest joys during the pandemic has been going to the Milpitas Library, even if I’m only there for three minutes, even when we can only do an outdoor pickup of our holds, even if I’m six feet apart from the nearest masked person. Though I can’t see most of their faces, I always feel a strong sense of camaraderie with my fellow patrons—almost all of whom are people of color, most of whom have kids in tow—and an overwhelming gratitude for the librarians who are stewarding these vibrant, essential community hubs.

Follow Chenxing Han at:

Website: chenxinghan.com

Facebook: cxhan

Twitter: @chenxing_han

Editing assistance by Molly Higgins.

Photo of author by Sarah Deragon.