Save Our Chinatown Committee in Riverside, Calif.: An Interview with Judy Lee, University of California, Riverside Librarian

by Melissa I. Cardenas-Dow

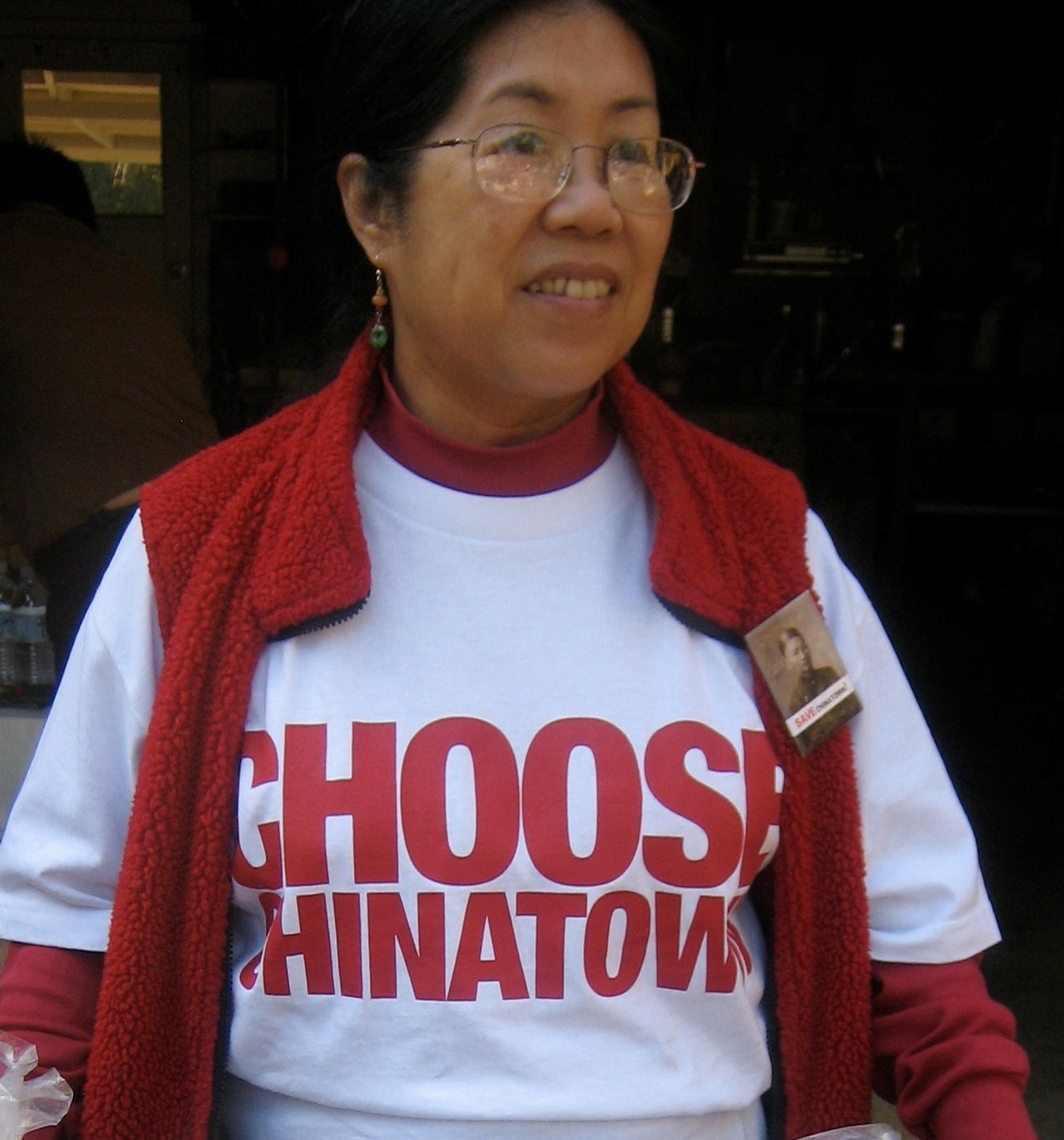

In late July 2012, I interviewed Judy Lee, University of California, Riverside (UCR) librarian and a founding board member of Save Our Chinatown Committee (SOCC), a grassroots community-based organization in Riverside, California. We talked about SOCC, its significance to local history and civic life, and the programs it holds and sponsors to highlight Asian contributions to American history and culture. This article is an edited version of our conversation.

Melissa Cardenas-Dow (MICD): What is SOCC? Why was it formed and what does it hope to achieve?

Judy Lee (JL): SOCC was formed around October 2008 as a last-ditch effort to save the Chinatown archaeological site in Riverside, California, and to protect Riverside’s Historic Chinatown from development that is incompatible with archaeological preservation. The group filed suit against the Riverside County Office of Education (RCOE), the City of Riverside, and the land developer to halt further excavation and destruction of the site. Riverside currently does not have a Chinatown, but there is a historic early Chinese settlement on the corner of Tequesquite Avenue and Brockton Avenue, near Evergreen Cemetery. The site is actually the second Chinatown in the City of Riverside. The first one was in the downtown area of the city, near Ninth Street, and was relocated in 1885 when city officials enacted ordinances that prevented Chinese businesses from operating in the downtown core area. SOCC members formed the committee in response to the Riverside City Council’s decision to accept the submitted Environmental Impact Report (EIR) in order to build a medical office building on the site. The group hopes to protect the site and erect a Chinatown Memorial Park to commemorate the contributions of the Riverside Chinese pioneers. Once the site is protected, I personally would like to see the group continue the cultural education mission for the community. This could include historical research and work to connect to a larger network of educators concerned with Chinese American and Asian American cultural education and preservation.

“Though we are focused on saving a particular ethnically linked site, membership in SOCC is multicultural.”

MICD: Why is it important to save a historic archaeological site like Riverside Chinatown?

JL: Several reasons. First, an archaeological site is a finite resource. Significant archaeological information gets lost when a site is disturbed. Looking at the site as it is right now, it looks like a vacant lot. Its significance is underground. Land development will disturb this area without the benefit of rigorous archaeological method, research, and study. Typically, developers only have time for and use salvage archaeology on their projects. Second, though the developer agreed to purchase the land from the current owners—the Riverside County Office of Education (RCOE)—there were many other sites and empty building spaces in the city of Riverside that could have been used for the same purpose. But Riverside has only one Chinatown. Once it’s dug up, it’s gone forever. Third, the value of the site itself has been documented to have four levels of historic significance. It is a city landmark. It is a county landmark. It is a registered historic place within the state of California and the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places. Fourth, we know that Chinese migrant laborers have contributed significantly to the development of citrus agriculture in the Riverside area (to name just one place and one industry) and to the economic history of Southern California. Citrus was so important to Riverside’s economic development that at one time Riverside was noted as the richest city per capita in the United States. The site is important historically and archaeologically. In fact, during the national registration process for the Chinatown site, Riverside Chinatown was remarked as one of the most intact archaeological sites of early Chinese settlements in the United States that reflects the connection between village life in rural China and migrant Chinese settlements during the same time period. The strength of this connection was a base for the Riverside Chinatown site’s inclusion into the National Registry of Historic Places. With the growth of citrus culture in Southern California in the late 1800s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture established a laboratory in Riverside, which eventually grew into the Citrus Experiment Station (1907). The Citrus Experiment Station was a center for the establishment of the UC Riverside (UCR) campus (1954). Today, UCR continues to be a leader in citrus research. The developer’s plans submitted for the EIR process required the demolition of the archaeological site. Many citizens thought the proposed development was troubling and that the Final Environmental Impact Report failed to answer many questions or to seriously consider proposed alternatives. Last, by demolishing the site we lose that sense of place, which is so important to a community and to American ethnic groups in particular, whose history and significance can often be overlooked or dismissed.

Recently, I attended the second Asian and Pacific Islander American National Historic Preservation Forum (APIANHP Forum), where a plenary session speaker left us with a Native American saying: “Wherever you go, you leave your breath behind you.” It can make a difference to those coming later to know who came before and that some of those people may have been like themselves.

“There’s a social justice element that accompanies the conviction of doing the right thing.”

MICD: Tell me more about the lawsuit and the latest developments.

JL: No one likes entering into lawsuits. We found ourselves in a David vs. Goliath underdog situation. Our lawsuit was an act of last resort since it was the only way we could stop the development of the site at that time. SOCC and the Riverside Chinese Culture Preservation Committee really tried to work with the Riverside City Council to come to some mutually acceptable compromise before the City Council voted to accept the Final EIR. At one point, the developer had agreed to be sensitive to the cultural and historical importance of the site and proposed to have a (static) display case of artifacts exhibited within the new medical office. Practically speaking, I don’t know how much of a benefit that would actually provide beyond window dressing, since the primary purpose of visiting a medical office building is not to learn about the history or culture of that area and the mounted display was not likely to evolve and change. The lawsuit filed by SOCC was done on the basis of CEQA (California Environmental Quality Act), which says that any historical, cultural, and archaeological significance to a site requires mitigating measures in order to proceed with any land development. But since the plans required complete excavation, the opportunity to gain archaeological information in situ would be lost. Not everyone understands that standard archaeological practice works primarily to protect sites because the relationships of where things are located relative to each artifact are important to the understanding of that culture. The developer was unwilling to move the building off the sensitive area of the site, that portion of the property that contained the main street of Chinatown which was the area listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The EIR didn’t address the CEQA mitigation requirement. The initial lower court ruling stated that the Riverside County Department of Education did not go through the necessary requirements to sell the land. At the appeal, the decisions of the lower court were reversed. The appellate court ruled that the EIR was not properly done, which is a win for SOCC. Now, the appellate court judges and the lawyers are working together for the final wording. The gist appears to be that the Riverside Chinatown site is protected for the time being. But something will need to be worked out and set in motion before long, or the threat of development can occur again.

MICD: With the 4th Appellate District Court’s ruling, what does SOCC have planned for the historic Chinatown site in Riverside, California?

JL: The purpose of SOCC when it was put together was to work on saving the Riverside Chinatown site from development incompatible with archaeological preservation. Our goal is to have a memorial or heritage park built on the site. At the moment, the SOCC, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, has hired a respected and experienced consultant and is exploring what might be possible. It would be great if a lot of different agencies, groups, individuals, and government officials became invested with this project as it really is about the city’s heritage and is important to us as a community.

“Once the site is protected, I personally would like to see the group continue the cultural education mission for the community. This could include historical research and work to connect to a larger network of educators concerned with Chinese American and Asian American cultural education and preservation.”

MICD: SOCC is more than just a grassroots organization focused on a single purpose, correct? What sorts of activities and programs does SOCC host and participate in?

JL: In the meantime, SOCC has done several things in the community to enhance appreciation of local history, cultural heritage, and relating these to many different levels and areas of civic life. For example, with regard to local history and cultural heritage and in addition to speaking to students and various groups, we hold an annual Chinese New Year Banquet fundraising event. We have also participated in other local community events. The most recent was serving as a George Wong level sponsor of Evergreen Cemetery’s Third Founder’s Day Front Row Fireworks event, staffing an SOCC booth at the event, and conducting free tours to George Wong’s gravesite, which is located on a slight incline at the southern end of Evergreen overlooking the Chinatown site. George Wong was the last resident and individual owner of Riverside’s Chinatown. Another booth we regularly staff is at the Mercantile Fair of Old Riverside Foundation’s Home Tour held each May. SOCC has sponsored a booth during past Riverside Juneteenth celebrations. We participated in the 2011 Dia de los Muertos celebration in Riverside with an altar to George Wong. We have worked with other community organizations for various events, such as with the Riverside Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League (Riverside JACL) and the Riverside Museum Associates’ Multicultural Council (Riverside Metropolitan Museum). Both Angel Island presentations by Judy Yung for the most recent Asian Pacific Islander Heritage Month (May 2012) and working with Riverside’s Human Relations Commission for Riverside’s first Day of Inclusion celebration (December 2011) are other examples of community partnerships SOCC supports.

One cultural event of note is the revival of the Chinese practice of Qing Ming in Riverside (Ching Ming in Cantonese), an annual festival when we pay respects to our departed ancestors. It’s similar to the Japanese Obon Festival and to the Day of the Dead/Dia de los Muertos. I’d like to think we have many more similarities than differences with area heritage groups when we hold cultural celebrations. Qing Ming shows many of these similarities. Translated as “clear brightness” from Chinese characters, Qing Ming is also known as Grave Cleaning Day. It is tied to the lunar calendar and occurs 105 or 106 days after the Winter Solstice, so it falls around early April. It is strictly a family-focused celebration. But it is also public in the sense that everyone does it at the same time. Families tend to the graves of their own family’s ancestors, usually those in direct lineage. There are food, flowers, incense, and the burning of paper money and goods. It is also a family picnic day. SOCC revived it as a day of public recognition to give people the opportunity to learn about the festival, customs, and the local history of the city of Riverside. We hold Qing Ming at Olivewood Cemetery to honor the pioneer Chinese Americans who died in the United States without descendants or other family members to remember them.

March 31, 2012 marked our fourth open public Qing Ming event. Representatives of the Gom Benn Village Society, the People’s Republic of China Consulate in Los Angeles, and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Council in Los Angeles (TECOLA) visited Olivewood and addressed the ceremonies. Most of the early Chinese pioneer residents of Chinatown were surnamed Wong and came from the village of Gom Benn. The Society has kindly invited SOCC to attend its annual Spring Banquets, as well as generously donated to SOCC for its efforts.

Though we are focused on saving a particular ethnically linked site, membership in SOCC is multicultural, a feature noted favorably when we were visited by one of the Consuls at the People’s Republic of China Consulate in Los Angeles. SOCC is invested in developing and nurturing multicultural ties among people of different cultural groups and backgrounds.

“Librarians are natural candidates for community participation: we’re organized, connected, communicative, and education-focused.”

MICD: What key pieces of information would you like APALA members to take away from our conversation? Professionally and personally?

JL: Right now, the story is ongoing, kind of a cross between “watch this space” and “you, too, can get involved.” We are open to ideas or examples of memorial projects that worked or were successful in conveying the history, memories, and stories of past contributions of Chinese or Asian American pioneers. And we can always use supporters to be “at the ready” for specific actions, both from near and from afar.

The next stage will likely entail fundraising. I was so glad that we achieved our 501(c)(3) status because our supporters can continue to contribute and get a tax break on their donations. Along the way we’ve experienced times of excitement, moments of outrage, heartwarming actions and response, and feelings of empathy and support, all elements of a good tale. At its center is the certainty of “doing the right thing.” It would probably take another interview to capture all of those emotions.

I’ve learned a lot from SOCC activities. First, it may sound like a cliché, but really, if it’s the right thing to do, one is compelled to do it. There’s a social justice element that accompanies the conviction of doing the right thing. That aspect can be appealing to some. Others may not see or understand that point of view. Second, there’s often a bigger picture, whether it’s in the political situation (like city politics or developer-city officials relationships) or how various facets of the community view local government in general or with regard to specific issues (like historic preservation, perceived favoritism, or handling of public funds). One may have allies in the larger community without knowing it. Third, through this struggle, I’ve discovered that one person can and really does make a difference. I can honestly say that each and every one of our board members has played an important role in saving the site. If we hadn’t worked together we would not have gotten this far. The odds were against us. The total is, indeed, greater than the sum of its parts.

This project has become intertwined with my life personally, professionally, and how I am involved in my community. My ethnic heritage relates to the Riverside Chinese of Chinatown. I am a second generation Chinese American whose ancestors come from the Toisan region of Guangdong Province. My parents are among the most recent immigrant generation to come to this country. If I had met George while he was still alive, I’m sure we would have understood each other’s dialect, even with my broken remnants of Toisanese, that dialect of Cantonese spoken by many of the early Chinese pioneers (like those who worked on the railroads, or came during California’s Gold Rush, or labored in agriculture or a laundry service).

“I want people to learn about this aspect of my community and to think “hey, I belong, too,” or “this is a rich community of which I am glad to be a part,” or “I didn’t know that, what an interesting place to be.””

JL: This effort ties in with my professional work as a reference librarian with selecting responsibilities for Asian American Studies at a university known for its diverse student body and with graduate students in anthropology/archaeology, U.S. history (and a public history program), sociology, and ethnic studies. I also serve on the University of California Chancellor’s Council on Climate, Culture, and Inclusion, the latest in a line of university service over the years addressing diversity issues. For me, the fight to save Riverside’s Chinatown site has opened up the world of preservation. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has redefined historic preservation to include heritage conservation and has made attempts to involve more Americans of various ethnicities to tell their stories and become a part of the American preservation landscape. As an educator, having this historical cultural resource available for the education of youth is important to me, both as something to pass on to my children as well as to the children in my community. I want people to learn about this aspect of my community and to think “hey, I belong, too,” or “this is a rich community of which I am glad to be a part,” or “I didn’t know that, what an interesting place to be.”

Librarians are natural candidates for community participation: we’re organized, connected, communicative, and education-focused. In a group setting, others gravitate toward the skills we have to offer. When Dan Tsang of University of California Irvine passed along the link to the 2011 Los Angeles Times article on Riverside’s Chinatown to a listserv, he referred to me as an activist librarian. Wow, Dan, thanks! Coming from a long-standing activist and role model of that caliber (and, of course, a librarian!), the comment tells me I’m heading in the right direction. Let’s hope that this story, our history, has a happy outcome. Librarians can be valuable partners. Librarians can be activists. Librarians can!

November 2012 update from JL: The Appeals Court issued a writ at the end of August 2012. It included an order for the City to make corrections to the EIR within 90 days or so, but no other specific instructions. We don’t know what the City intends to do, what their timetable is, or whether there will be an opportunity for public comment.

SOCC’s current chair, Rosalind Sagara, received the NTHP Aspire Award (National Trust for Historical Preservation) at their recent annual conference in early November 2012. The information was released in our newsletter and covered in an article I wrote and published on the SOCC website.

SOCC participated again, our second year, in Riverside’s Dia de los Muertos Celebration with an altar to George Wong. We also distributed our popular handout comparing Ching Ming (Qing Ming) with Dia de los Muertos. This time the photo of George Wong included the story of his driving out the KKK from Chinatown with a shotgun. That, too, was interesting and popular. Many took photos. The Riverside Food Co-op participated for the first time and wanted to pay homage to the Chinese pioneers for their role in area agriculture and the citrus industry with their altar. They were in touch with our committee before the event.

Many thanks to Judy Lee for her time and support. Photo images courtesy of Judy Lee and Save Our Chinatown Committee (SOCC). For more information about SOCC and the historic Chinatown archaeological site in Riverside, California, please visit the SOCC website and the SOCC Facebook page.

Melissa Cardenas-Dow is the Outreach/Behavioral Sciences Librarian at University of Redlands in Southern California.