by Dawn K Wing

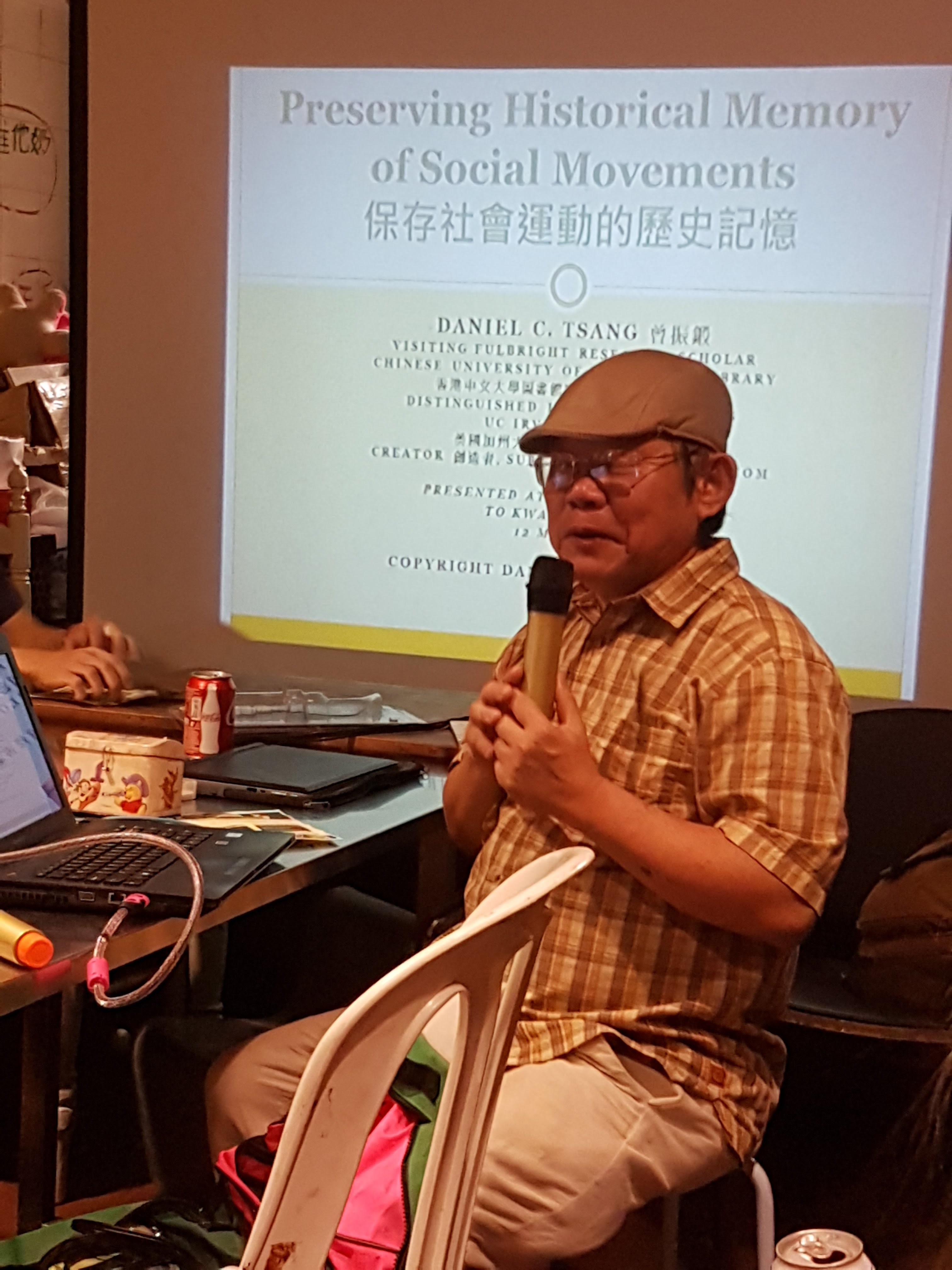

Daniel Tsang is distinguished librarian emeritus and retired librarian at UC Irvine. Daniel has been doing field research on the preservation of protest culture in Hong Kong, and received a Fulbright scholarship a couple years ago for this project. You can learn more about his previous work in his interview with Melissa Cardenas-Dow in 2015.

Dawn Wing (DW): What motivated you to apply to the Fulbright Scholar Program to do research on preserving protest culture in Hong Kong?

Daniel Tsang (DT): I realized it was a unique opportunity to match my existing research on protest material stemming from my days of writing for the alternative press and my own identity as a Hongkonger.

DW: How did you develop a relationship with the host institution, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), where you conducted your research?

DT: By luck in 2016, I [was] seated next to the CUHK University Librarian Louise Jones at a sumptuous seafood banquet in Sai Kung kicking off the Academic Libraries conference at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. I eventually asked Dr. Jones if CUHK Library could be my host institution for my Fulbright research, and she readily and kindly agreed. [It] turns out the library has a nice Umbrella Movement collection.

DW: Describe your experiences doing research in Hong Kong during the recent protests against the Chinese government.

DT: My research under the Fulbright grant was from 2017 to 2018 before the current protests had even started in 2019. In my ten months at CUHK I had a wonderful time interviewing veterans of earlier clashes with the Hong Kong government in the Umbrella Movement (2014) and subsequent Fishball Rebellion (2016). I managed to interview key activists, such as Hong Kong University Law Professor Benny Tai who is currently out on bail after being imprisoned, localist Edward Leung who is currently imprisoned for six years, and his fellow comrade Ray Wong who is now in exile in Germany. I also gave public talks at CUHK Library, Hong Kong University Library, and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. I was interviewed by Lenny Kwok, Hong Kong’s first indie band founder, for a Cantonese-language column in the Sunday Ming Pao, a local daily. We had met at the first Black Book Fair in Hong Kong. I also especially enjoyed giving a talk at Fixing Hong Kong, a community-based organization in a working class neighborhood, Tokwawan, in Kowloon. I was glad to “give back” to the community a little of what I knew. Incidentally, the current protests are against the Hong Kong government as well as Beijing’s interference, but they occurred after my grant. Although I’ve returned to Hong Kong periodically on my own and continued my research.

DW: What are some challenges and innovations you discovered during your research in regards to preserving protest culture in Hong Kong?

DT: As I told Lenny [Kwok] in Ming Pao, activists are seldom archivists and vice versa. But I found that, like in other locations, artists are at the forefront of creative protest actions, and some of that output has been preserved at places such as Asia Art Archive and CUHK. One sketch artist, Fong So, has even donated his sketches of the Umbrella Movement abroad, to the British Library. But I fear a lot of protest literature remains squirreled away in homes and computer or cell phone storage; although for the current protests, CUHK is committed to creating a public digital archive eventually. Thus, the challenge remains to let more people know that just posting something online is not “archiving” it.

DW: How did your work as a librarian and digital archives administrator at UC-Irvine inform your Fulbright research and vice versa?

DT: The main thing I realize after three decades as a social science data librarian, and lately as an administrator of UC Irvine’s web archiving efforts until I retired in 2016, is that web archiving, as well as data archiving, requires a sustained commitment of time, resources, and personnel for it to last. In particular, these digital resources need to be carefully curated.

DW: How did your first Fulbright research experience in Vietnam connect with the research you are now doing in Hong Kong?

DT: I was actually the first data librarian to serve as a Fulbright Research Scholar. In 2004, I was based at the Institute of Sociology in Hanoi, where I attempted to research what happened to the research datasets generated by local and foreign social scientists in Vietnam. The experience taught me that before “archiving” can happen, many challenges must be overcome, including [those that are] political. Politics definitely overshadowed [my] later efforts at preserving protest literature in Hong Kong.

DW: What advice do you have for APALA members who may be considering applying to do research through the Fulbright Scholar Program?

DT: Think of a doable project and which local institution can serve as host. Cultivate librarians, academics, or community leaders, especially [those] who can write letters of recommendation. Then, in your written proposal, be succinct and clear about why your project is something worth the federal support and what the project hopes to achieve.

DW: Other thoughts or comments you wish to express?

DT: Remember the U.S. Scholar Program is for U.S. citizens seeking to serve abroad. It’s an amazing opportunity to live abroad and experience hopefully something new. Teaching and/or research options are available.

Editing assistance by Shelly Yuki Black.