SAADA: “An investment in our past is an investment in our future.”

by Melissa Cardenas-Dow

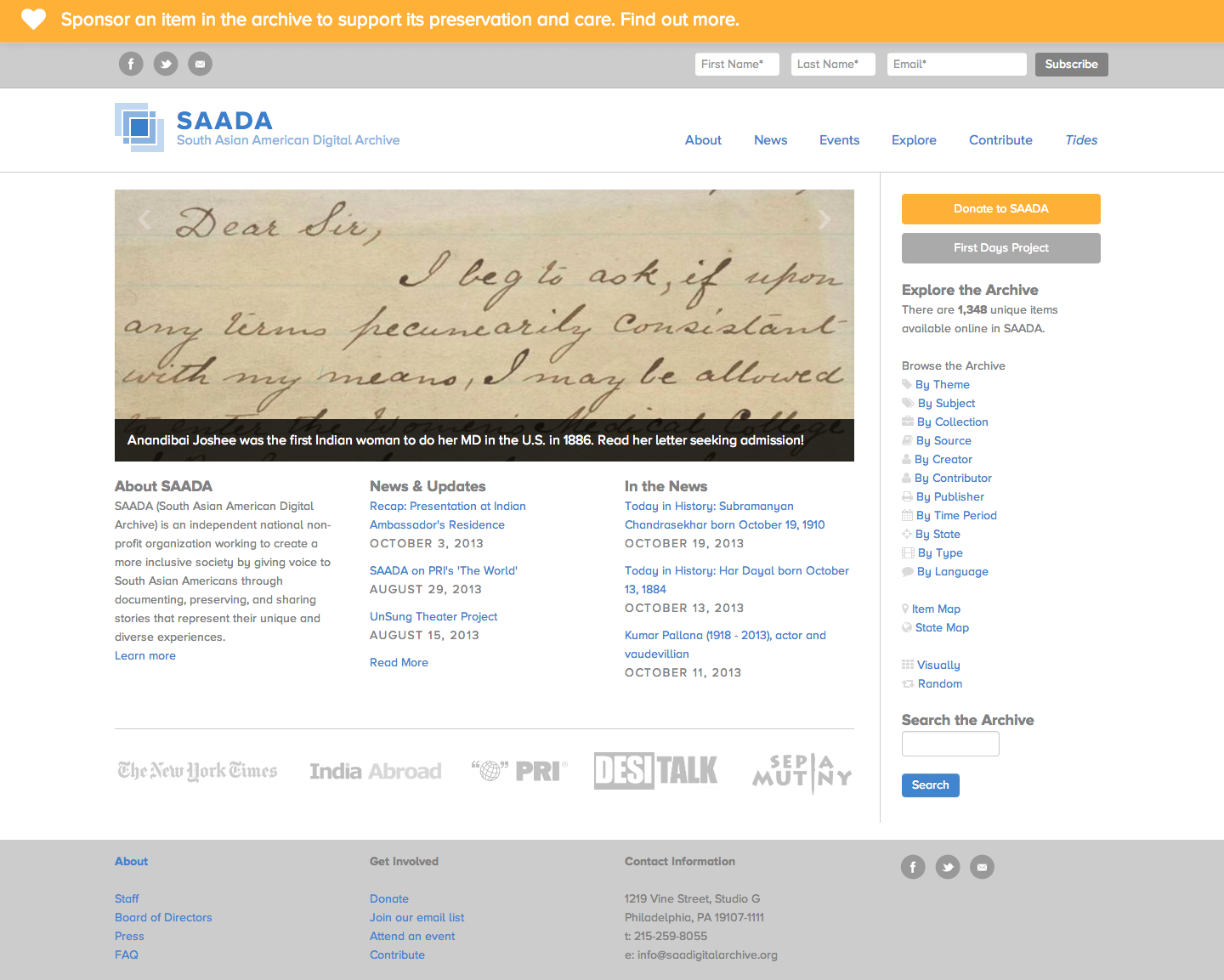

To find out more about SAADA (South Asian American Digital Archive), I conducted a phone interview with Samip Mallick, SAADA’s Co-Founder and Executive Director, on August 21, 2013. SAADA is an independent nonprofit organization working toward a more inclusive society by giving voice to South Asian Americans through documenting, preserving and sharing stories that reflect their unique and diverse experiences. SAADA focuses on digital information and is primarily an online entity but is physically based in Philadelphia. The following article is excerpted from our conversation.

Melissa Cardenas-Dow (MICD): Tell me a little bit about the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA) as an organization. How did it come about?

Samip Mallick (SM): SAADA was founded in 2008 by me and Michelle Caswell. At that time, we were both working at University of Chicago in different capacities. Michelle is now an Assistant Professor of Archival Studies at UCLA. Michelle and I realized that materials related to South Asian American communities were not being systematically documented and collected by any traditional repositories. We felt that these histories were being overlooked, and over time, in danger of being lost. My background is in computer science and Michelle’s is in archival studies, so we also realized that we could combine our backgrounds and create a powerful model for documenting South Asian American history. Out of these conversations, SAADA was born. SAADA is a way for us to make a contribution to documenting, preserving and sharing the stories of South Asians in the United States.

MICD: Are you affiliated with any other institution? Tell me a little bit more about how SAADA provides access to its digital objects.

SM: SAADA is an independent, nonprofit organization, but we definitely work very closely with institutions around the country. Our archive uses a post-custodial, digital-only model. This means that we don’t take physical custody of any archival materials. Instead we work closely with community members, organizations, and institutions to digitize and provide access to materials relevant to the South Asian American community. The physical materials, however, stay with the individuals, organizations or institutions from which they originate. One of the great strengths of this model is that it allows us to work collaboratively with many different groups around the country that may have relevant materials in their collections. We are then able to provide access to these disparate materials and create awareness about them in one online location. All the materials we collect are freely accessible through our website. In addition to the digital objects made available for web browsing and viewing, we also have high resolution objects that are meant for long-term digital preservation, which are not available for public web access. These two types of digital objects that we house represent the two parts of what we do: provide access and preserve histories for the long-term.

MICD: What do potentials users need to do if they require the higher resolution objects?

SM: For those who are interested in using our digital objects from our public access website, they certainly can do that. Materials from the archive have been used for individual scholarship, documentary films, lesson plans, research, blogging, creative works and many other formats. For those who require higher resolution and higher quality digital objects, we encourage them to contact us directly. Should we not have the permissions necessary for the use of the high resolution files, we direct users to the institutions or groups who hold copyright. Once permission has been granted, we grant access to the higher resolution files. One such instance like this happened recently. A documentary filmmaker wanted to use higher resolution files of images he found in SAADA. We put him in touch with the rights holder of the images, who was a descendant of the creator of the images. The rights holder granted permission and we released the high-resolution files to the filmmaker, which were then used in the documentary film.

MICD: SAADA’s mission, then, really, seems to be two-fold: First is the more technical aspect of working with digital objects: provide access and preserve materials that serve to document South Asian American history. Second is to help educators, researchers, writers, journalists and South Asian American community members to become more aware of individuals, groups, organizations and institutions that may have these materials or knowledge of the community’s history and stories. Do I have that right?

SM: Yes, that’s right. Besides providing access to materials, we also aim to raise awareness to the stories of South Asians in the United States–to make them relevant today, to both members of the South Asian American community and to the general public. We do this not just through the SAADA website, but also through events, through media, through outreach and educational programming. We attempt to use a variety of ways to raise awareness of the stories and contributions of South Asians in the United States; how they are an integral part of the American historical narrative. In many ways, we have gone far beyond just archiving and documenting materials. We’ve moved toward thinking about the usefulness and relevance of SAADA to various communities today.

There are many of us in the South Asian American community who are not aware of these stories, so raising awareness is not just a matter of academic interest. For me, it’s a very real problem that the community itself doesn’t have access to its own stories. As an organization, SAADA can play a role in connecting people with their own history. What’s amazing and fascinating is that interest comes not just within the South Asian American community, but from across the world. We’ve had nearly 150,000 unique visitors within the last year alone. And more than half of this traffic comes from outside of the U.S. Much of it comes from South Asia–countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal. Most there do not know much about the diaspora communities in the United States and are learning about these histories for the first time.

MICD: Speaking of outreach and educational programming, are there particular outreach or educational projects that SAADA would highlight in particular?

SM: One recent project that we’re really excited about is SAADA’s First Days Project, where we ask community members to submit their stories about their first day in the United States. What inspired this project was realizing how often I would hear from an individual about their first impressions of life in the United States, remembering a time in their life that was maybe 30 or 40 years ago. Somehow these memories from many years prior were crystal clear for them. So we wanted to create a way to capture these stories, and through the snapshot of one day capture the intimate details of arrival that are otherwise lost in the grand sweep of history. We have had more than 80 stories submitted to us already and more coming in every day. It’s been an incredibly rewarding experience to be able to capture and document an incredibly poignant moment in a person’s life.

As an organization we will continue to think creatively about how we can document, preserve and share stories from South Asian Americans and ensure that these communities are included in the narrative of what it means to be American.

Many thanks to APALA Board-Member-At-Large 2013-2015 Anna Coats for paving the way to making this article possible.

Editorial assistance provided by Jeremiah Paschke-Wood.