Leza Lowitz, together with Shogo Oketani, is the co-author of “Jet Black and the Ninja Wind”, which won APALA’s 2013-2014 Young Adult Literature Award. Last November, Leza and I wrote each other via e-mail about how identity, family, and home influence her writing.

– Alyssa Jocson Porter, Web Content Editor

Alyssa Jocson Porter (AJP): Please introduce yourself and briefly describe your literary work and career path to date.

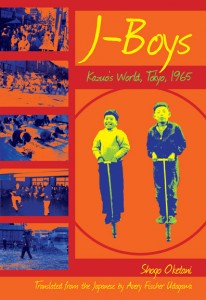

Leza Lowitz (LL): I’m an American living in Tokyo, where I write and also run a yoga studio. I’ve published 18 books in a variety of genres, from young adult to memoir to poetry. I often write with my husband, the middle grade novelist Shogo Oketani (www.j-boysbook.com). Only occasionally do we drive each other crazy. I like to joke that other couples finish each other’s sentences; we finish each other’s books. Most of my books have to do with finding a home in the world, wherever you are.

AJP: When we talk about diversity, we often discuss the differences that are immediately noticeable — ethnicity, gender, age, culture, etc. How have these played a part in your writing, e.g. in “Jet Black and the Ninja Wind”, winner of APALA’s 2013-2014 Young Adult Literature Award, or in your new book “Up From the Sea” (release date January 12, 2016)?

LL: Shogo is Japanese, and I am American. We have an international marriage, and are raising a bicultural child. We want him to read books that reflect his world.

Among other things, diversity means “variety.” I’ve lived in Japan for over a decade, and during that time, I’ve met many different kinds of women; but there wasn’t much variety in the way Asian girls and women were portrayed in Western literature. When “Memoirs of a Geisha” came out, Shogo and I were motivated to counter these stereotypes. We wanted to write about a strong half-Japanese female warrior. Women were not allowed to be samurai, but they were ninja. Since their identities were hidden, their stories were untold.

I’d always thought of ninja as B-grade Hollywood assassins (or turtles), and to be honest, I was not very interested in them. Shogo believed ninja were most likely tribal people who developed secret arts to protect themselves against invading forces. The story of Japan’s indigenous Emishi tribe mirrored Native American history, so we connected Japanese tribal lore with the story of some special modern warriors — the Navajo Code Talkers. In “Jet Black and the Ninja Wind,” the two tribes come together to help Jet save her ancestral land. We hope readers will learn more about these true American heroes while discovering the real face of the Japanese ninja.

The massive earthquake and tsunami struck Japan on March 11, 2011, while we were writing “Jet Black.” Shogo decided to stay to take care of his elderly father, so I stayed with him and our six-year-old son. Like many others, I wanted to help, so I went to the disaster-stricken area of Tohoku to volunteer. Major aftershocks rocked the area daily, and the nuclear plants leaked dangerous radiation, so I felt an urgency to write down everything I experienced. The brave children I met in the disaster zone inspired me to write “Up from the Sea,” a novel in verse about Kai, a multiracial boy who loses nearly everyone and everything he cares about on that day. Everything, that is, except hope.

The massive earthquake and tsunami struck Japan on March 11, 2011, while we were writing “Jet Black.” Shogo decided to stay to take care of his elderly father, so I stayed with him and our six-year-old son. Like many others, I wanted to help, so I went to the disaster-stricken area of Tohoku to volunteer. Major aftershocks rocked the area daily, and the nuclear plants leaked dangerous radiation, so I felt an urgency to write down everything I experienced. The brave children I met in the disaster zone inspired me to write “Up from the Sea,” a novel in verse about Kai, a multiracial boy who loses nearly everyone and everything he cares about on that day. Everything, that is, except hope.

Climate change causes great devastation, but it can also bring us together in remarkable ways. Children from Tohoku, Japan, went to New York to meet with young survivors of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina for mutual support. As these children showed, there are many ways to reach out to others across cultures, borders or language. I hope the novel will remind kids of the ways we can help each other in times of disaster and tragedy, even across oceans.

AJP: How do you think your personal identity, family, and home (Japan) influence your writing and/or the diversity of your readership?

LL: I grew up in the 1970s in Berkeley, California — the most liberal place on the planet at that time. I went to Malcolm X Elementary school, one of the first schools in America to voluntary integrate. We were visited by amazing writers like Maya Angelou and James Baldwin. As a young fifth-grader sitting on an auditorium floor, the undeniable power of their words brought the fractured audience together. Stories were powerful tools of healing. This was seared into my brain. Later, I studied meditation and martial arts, which ultimately led me to Japan and to meet Shogo. San Francisco is very much a part of the Pacific Rim. Asian culture has defined so much of the richness and beauty of the West Coast, and Asia never felt far away.

Shogo grew up in Tokyo, in a house of books. His father is a literary critic and professor, whose home library was filled with books in many languages — Russian, Chinese, German, French, English, Japanese. Exposure to world literature at a young age broadened both his perspective and sparked his curiosity about the bigger world.

As an adult, living in a foreign country (especially a notoriously “closed” one like Japan) has given me daily challenges from language to culture to customs. But it’s helped me grow in ways I could never have imagined, caused me to reexamine how I define myself beyond skin color, religion, culture.

We live in an increasingly international, multicultural world and have to find bridges of tolerance and understanding. Humility, respect and appreciation are going to carry us into the future in a peaceful way.

We live in an increasingly international, multicultural world and have to find bridges of tolerance and understanding. Humility, respect and appreciation are going to carry us into the future in a peaceful way.

Shogo and I hope that readers will take this away from our books for young readers. In truth, we are all connected. Literature underscores this deep connection and reminds us of universal truths and the desire for freedom, peace and understanding that unites us all.

AJP: You’re being interviewed by a librarian, for an audience of progressive Asian American librarians. What are your thoughts on libraries, and their place in building diverse communities?

LL: Like every writer, I was a reader first. When I was seven, my mom took me to the San Francisco Public Library. We would climb the red brick stairs and walk along a path to a stately, colonnaded Italian Renaissance building. To me it was magical. I thought the library was a castle — I still do. On those shelves, I found books about worlds I could only dream about. I read stories about people who had survived war and famine and tragedy. I read stories set in China, France, India, Arabia. Those books made the far world seem closer.

It took us 15 years to write and publish “Jet Black and the Ninja Wind.” During that time, libraries around the world provided sanctuary and resources. In West Marin, California, we looked forward to every first and third Wednesday, when the “Free Library” wheeled its way up Coastal Highway 1 and pulled into our town. This mobile library always had the best books and the happiest librarians. We read hundreds of books to research this novel, many borrowed from libraries.

Years later, a local library in Tokyo gave us hours of quiet time to write and edit while our son played soccer with his team at a nearby field. Even though you shouldn’t even talk in a library, our novel was conceived in a library.

We were also happy to be able to help build a library in the tsunami-affected region. It is so important to have a sanctuary — a quiet space to read, imagine and dream.

AJP: What advice would you give new professionals (writers or librarians), especially those from diverse backgrounds and/or those who work with diverse populations?

AJP: What advice would you give new professionals (writers or librarians), especially those from diverse backgrounds and/or those who work with diverse populations?

LL: For writers, find your voice and resolve to tell your story your way. Most of writing is revising, so don’t be afraid to work very hard for a very long time, probably with little to no recognition. Write because you have a burning story to tell. Join a writing community or organization like

Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) and learn from the considerable wisdom and experience of others. Be inspired! Get feedback and give feedback, too. Trust your story to take shape in its own time.

For librarians, keep doing what you’re doing — changing lives one book at a time. Libraries are the original World Wide Web — no one does more to bring together diverse communities.

Editing assistance provided by Jeremiah Paschke-Wood.